Sushant Bharti

The Social context of Eighteenth-Century Vrindavan through the Eyes of Nagaridas

Poems are not only the manifestations of a poet’s emotions regarding a certain subject. Such compositions sometimes also embed a lot of other important information. A case in point involves the poetry of Maharaj Sawant Singh Ji of Kishangarh, also known as Nagaridas. His padavalis, titled Braj Jana Prashansha, provide some critical information about various occupations which were then practiced by the inhabitants of Vrindavan. The temple town of Vrindavan, which effectively started to evolve during Mughal supremacy, was a full-fledged town thronging with many activities when Nagridas came to Vrindavan after renouncing his kingship. The town’s economical aspect along with the presence of various sections of societies who were then its inhabitants can be easily seen in his work. The descriptions given by Nagaridas are very interesting because they are carefully woven together with the idea of bhakti, in that he emphasises each and every person’s importance in the town. I aim to throw light on Nagaridas’s poetry in the context of the social and economic fabric of eighteenth-century Vrindavan.

Annalisa Bocchetti, University of Naples “L’Orientale”

Soī citerā, yaha jaga citra kīnha jehi kerā…:

The Symbolism of Painting in the Citrāvalī by Usmān (1613 CE)

The Avadhī Sufi romances (premākhyāns) have long been performed throughout North India since the fourteenth century following the inauguration of the genre by Maulana Dā‘ūd. The Indian Sufi poets have used both Indic and Persian poetics to communicate their mystical views to indigenous and multicultural audiences.

Usmān continues this literary tradition in his Citrāvalī (1613 CE), narrating about human love as an allegory of divine love. Therefore, the hero’s quest for his beloved, viewed as the reflection of divine light and beauty, becomes a metaphor for the seeker’s mystical journey.

However, Usmān introduces a new aesthetic and theological element in his text that still needs to be explored within the symbolic and literary context of the premākhyān genre. Indeed, a central motif of the poem is the picture or painting (citra), through which the poet conveys complex notions of Sufi ontology starting from the material dimension of art. Thus, he attempts a verbal representation of the Creation as divine artwork, imagining God as a Painter who portrays ‘the picture of the world’. By linking the heroine with the divine element, he draws upon the artistic imagery, representing her as an artist woman (citriṇī) painting her self-portraits in her palace’s picture gallery. Pictorial imagery is also employed to describe the magical encounter between the lovers, resulting from the sighting of the beloved’s portrait (citra-darśana).

While painting has been a recurring theme in Indo-Persian literature, this paper examines the original recreation of mystical aesthetic terminologies in an understudied Sufi text of early modern North India. Through highlighting the various key terms (citra, mūrti, rūpa…) of art and visual semantics employed in the poem, this paper aims to illustrate how the poet explains the Sufi axiom of the multiform cosmos and the unity of Allāh (waḥdat al-wujūd) through a distinctive poetic language.

Abhishek Bose, University of Calcutta

Cruel Krishna, Caring Krishna: Of Signatures and Metatext in Vaishnava Padāvali̅

Padāvali̅(songs/short poems) as a literary genre is closely associated with the expression and aesthetic of Bhakti. Though Padāvali̅ has various usages and can be found to span the entire Indian sub continent, one of its highest points in terms of variety, magnitude and intricacy is certainly Vaishnava Padāvali̅. This sub-genre is closely connected with the emergence of the Chaitanya sampradāya in Bengal; however, the medium of composition is not confined to Bangla alone, these are composed in Oriya, Brajabuli, Brajbhasha and even in Sanskrit. Through centuries, anthologies have been compiled; aesthetic theories have been developed solely focusing on the rasa in Padāvali̅. Moreover, these are performed texts; the verbal language is complimented with music, singing, narration, enactment. Beside this public life of Padāvali̅, there is an esoteric or metaphysical aspect. The devotees depend on these compositions for the remembrance of the li̅lā of Radha and Krishna – arguably the most advanced stage of sādhanā in the Chaitanya/Gaudiya sampradāya and hence Padāvali̅ is accorded a special, other-worldly status. Hence, the authors are regarded as Mahājana, literally great person. In these schema, authors are not ‘imagining’ the li̅lā, they are actually ‘witnessing’ the events; they are present in the eternal bower of Radha-Krishna, seeing the unfolding of events themselves, narrating the commentary. Given this real status of Padāvali̅, the bhanitā or signature line at the end of the composition is not only about the author’s ownership, it is also an attestation of authenticity. Though bhanitā is common to many genres and languages, it thus becomes crucial to Vaishnava padāvali. It can comment upon, explain, and even object to the content of the composition. This presentation seeks to explore the metatextuality of signature in Vaishnava Padāvali̅, by closely reading one such composition.

Winand M. Callewaert,KU Leuven

“The Callewaert Collection“

In 1971 (51 years ago) I had spent seven years studying in three Indian universities and I came back to my hometown Leuven in Belgium. For one year I went then to Paris to attend the classes of prof. Charlotte Vaudeville at the Sorbonne.

One day she told me: „Winand, if you want to do something worthwhile with your research career, go to Rajasthan, look for Dadupanthi manuscripts, copy and edit the texts and make a selective translation. And while you do that, look also for other manuscripts“.

How do you find manuscripts in remote temples and collections in Rajasthan, in the seventies of the previous century? Drink tea drink tea and drink tea.

The result of the travelling all over India and drinking tea for thirteen years is now a databank of 15.000 exposures, digitized with a grant of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, with the help of its senior research fellow dr. Jaroslav Strnad.

In that databank, called „The Callewaert Collection“ a copy is preserved of 94 manuscripts, copied in 15 different places.

Not a few of these manuscripts have now disappared or are in a hopeless condition or are no longer accessible.

Before the end of 2022 I hope to prepare a detailed list of contents of all these digitized manuscripts and Jaroslavji will make the scans available on the website of the Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences, Prague.

In my contribution to the Osaka Bhakti Conference I intend to discuss in more detail what is available in this Databank.

I also want to turn to the future. Even today, everywhere in India, hundreds of manuscripts disappear through decay or because business people use the old paper to produce copies of old paintings painted by modern young artists. In the field of Bhakti literature many treasures are waiting for the brave adventurer ready to drink tea and drink tea and negotiate.

Stefania Cavaliere, University of Naples L’Orientale

A new ethical and philosophical education for the Princes of Mughal India.

Moral allegories in court poetry from the 16th and 17th centuries

Court poets connected to the imperial and sub-imperial courts engage in writings on moral and philosophical themes in their compositions. Either as a section on nīti as in Rahīm Khānkhānā’s verses or as independent works for moral education such as Kavīndrācārya Sarasvatī’s Kavīndrakalpalatā written as a “mirror for the prince” Dara Shikoh, of whom he was a tutor. We can hypothesise a transitory phase in Keśavdās’s Rāmacandrikā where moral allegories are used by Vasiṣṭha while teachings to Rāma how to become a jīvanmukta.

The reference models seem to be always the same. They come from some of the most important texts of this historical-cultural and religious phase of India, including Yogavāsiṣṭha and moral allegories such as the Prabodhacandrodaya. From a philosophical point of view, these moral allegories offer a compendium of classical philosophy – mainly focused on Vedānta open to devotional influences – recalling the practice in vogue at that time in imperial and sub-imperial courts of translating/adapting classical philosophical texts from Sanskrit into Persian or the vernaculars. From the historical point of view, the various examples of Hindu intellectuals transmitting classical models for the education of Mughal princes demonstrate their influence and authority.

Observing similar models in parallel literary sources, we can keep how – along with the circulation of intellectuals, ideas and texts – a composite canon of texts for the education of the princes was created and circulated among the courts belonging to the Indo-Islamicate milieu. It resulted from the combination of doctrines from different religious traditions tailored to the needs of the courtly audience, proposing a new educational canon for the kings of 16th and 17th century India.

Christopher Diamond, The Australian National University

Poetic Villains and the Making of Maithil Kings in Vidyāpati’s Padāvalī

A stranger in the doorway, a thief in the night, or a jilted lover spreading lies — the villains of early Maithili lyric poetry are compelling in their portrayals of masculine poetic vices and virtues. While the masculine hero (nāyaka) is ubiquitous in the poetic landscape of most Bhasha/vernacular texts of North India, the poetic villain (dujana/piśuna) is less well understood. What role does the poetic villain play within the character landscape of vernacular poetry in Mithila, especially in the works of Vidyāpati (c. 1360-1450 CE), and for the patrons of this tradition? The villains of the early Maithili poetic universe provided mirrored images (pratyudāharaṇa) from which the elites of the region extracted models for illegitimate masculine power (men who are “animals without a tail”) and idealised masculinity through its inverse (the supuruṣa). Vidyāpati’s characterisation extends beyond the poetic character of his Maithili lyrics into the less-than-ideal men of his ethical treatise in Sanskrit (the Puruṣa-Parīkṣā) and historical narratives in Avahaṭṭha (the Kīrttilatā).

The frequent occurrence of these dastardly characters lends us to believe that ideal Maithil [elite] man was not only an aesthete (or rasika), but also a fully realised ethical paragon (supuruṣa) in the real world. Vidyāpati identified his patrons, the early rulers of the Oinvāra Dynasty, as the definitive uniters of aesthetics and ethics. This supuruṣa/piśuna duo also became an attractive model for other would-be elites of the extended region of Eastern India in the subsequent centuries. My analysis of the poetic villain’s characterisation in Maithili and theorisation in Sanskrit demonstrates that aesthetic and ethical concerns were central to regional identity making for the elites of Mithila to map themselves onto a network of aesthetic-ethical elite power in the east of South Asia.

This paper builds upon the concept of a literary tradition by looking at the thirteenth-century Prakrit Ṣaṣṭi Śataka by the Śvetāmbara Kharatara Gaccha Jain layman Nemicandra Bhaṇḍārī. Over the subsequent three-quarters of a millennium this text has been the subject of Maru-Gurjar Bhasha vernacular bālāvabodhs (the first in 1440), Sanskrit ṭikās (the first in 1501), and vernacular translations and commentaries in Maru-Gurjar, Gujarati, Marwari, Braj Bhasha, Dhundhari, and various forms of early modern and modern Hindi, by both Śvetāmbara and Digambara authors. This tradition includes seventeen texts by named authors, and several others by anonymous authors. The text very quickly moved out of Kharatara Gaccha literary circles into Tapā Gaccha ones, and then in the eighteenth century was translated and commented upon by Digambara authors, who knew it as the Upadeśa Siddhānta Ratnamālā. Almost every one of the authors in this literary tradition composed texts in multiple languages, or in other ways demonstrated high degrees of multilingual fluency, beginning with Nemicandra Bhaṇḍārī himself, who also wrote in Apabhramsha. This paper, therefore, argues that to better understand South Asian multilinguality, we need to look not only at times and places where different authors wrote in different languages, but also at individual authors who demonstrated fluency in two or more different languages. Further, given the significant percentage of Jain authors in the medieval and early modern periods wrote in multiple languages, we see an alternative definition of cosmopolitanism from that of Pollock: to be a cosmopolitan Jain author was not to write in the single trans-regional language of the Sanskrit cosmopolis, but rather to be able to write in multiple languages.

Florence Pasche Guignard, Université Laval

Maternal figures and engagement in bhakti in two Vaiṣṇava hagiographic collections: A matricentric feminist reading in religious studies

Many women recognized as saints in the bhakti traditions of premodern India follow a path that leads to a union with their chosen divinity in the mode of “sweet” love (mādhurya bhāva) between the devotee and her beloved and lover (a god, most often thought of as male). Like Andal, Mirabai, Akka Mahadevi, and others, they reject human marriage to a man and the valued roles of wife and mother, with their attendant material benefits, and prefer engaging in a spiritual path, often outside of institutional settings (e.g., monastic). Devotion in the mode of parental or motherly love (vātsalya bhāva) is, however, also a possibility for some women who have chosen a religious life outside the norm. From a perspective in religious studies and through the lenses of matricentric feminist theory, this paper will examine selected allusions to devotion in the maternal mode in the hagiographic collections Caurāsī vaiṣṇavan kī vārtā (84VV) and Do sau bāvan vaiṣṇavan kī vārtā (252VV), the lives of the respectively 84 and 252 devotees in the community of Vallabha (16th-17th c. CE). Beyond notions of “gender” and “femininity,” I focus precisely on “the maternal” to discuss, first, the entanglements and provisional disruption of notions of im/purity after childbirth and matrescence in this devotional context, as reflected in the hagiographic narrative about Vīrbāī (vārtā 61 of the 84VV). Then, I engage in a matricentric reading of vārtā 83 of 252VV, about a child-widow who engages in devotion to Kṛṣṇa through providing maternal care to him as a young son. I will then situate such figures in comparison with other non-maternal figures of bhakti and conclude with comparative considerations useful to the broader study of the intersection of motherhood/mothering and religion/s through literary sources such as hagiographic collections.

Jack Hawley, Barnard College, Columbia University

Poetic Selfhood and the Copyright Raj

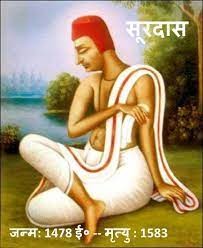

Recently I have been trying to piece together the process by which certain images of Surdas have come to dominate the popular imagination in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In this presentation I will direct my attention to one of the most prominent of these:

I will show that the explicit history of this image stretches back almost to the beginning of Indian self-rule (1947), but what about before that? Please stay tuned.

But here’s a question: Am I allowed to express these findings in print, given international legal canons governing rights and privileges of reproduction as they relate to paint, print, and digital reproduction? The manner in which these tussle with canons of literary self-representation surrounding the institution of the oral “seal” (chāp) appropriate to early modern Hindi or Brajbhasha pads is worth a moment’s reflection. In addition, am I defying “rights and privileges” norms by repurposing parts of an earlier presentation (in MSWord and Zoom form, October 2021) for this July 2022 avatar?

Monika Horstmann, University of Heidelberg

‘All who do not recognize Guru Gorakh are heretics’ (Prithīnāth)

Prithīnāth (16th century) belonged to the Nāth Siddha tradition, represented in vernacular compositions and transmitted first in the beginning of the seventeenth century in Dādūpanthī manuscripts. In size, Prithināth’s writings come next to those of Gorkhnāth of the same tradition. Prithīnāth composed numerous didactic treatises in which he refers to the authority of Gorakhnāth. This raises the question of his understanding of yoga as the essential aspect of Gorakh’s teaching. Prithīnāth does not always treat the yogic process rigidly, but rather highlights aspects of it in individual treatises. An exception to this can be expected to be found in his several compositions following a serial format, such as ascending numbers or the calendrical cycle. These compositions are examined before the background of the rest of the author’s treatises. This allows for distinguishing the Nāth Siddha concept of yoga, as represented by Prithīnāth, from the haṭhayoga usually associated with Gorakhnāth. It rather relates to concepts distinct from haṭhayoga. The result of this exercise is consequential for understanding why the Sants acted as trustees of the Nāth Siddha tradition.

Heleen De Jonckheere, The University of Toronto

“Let me tell you about the origin of śrāddha.” Early-modern Jain perspectives about death rituals.

The cyclical perspective of life within Jainism, similar to other traditions originating in India, makes the transition of death, either as redeath or as final liberation, a moment of particular importance. Jains believe this transition is instant and therefore hold an opinion different from Hindus and Buddhists according to who a period of time lapses before a soul is reborn. This paper wants to zoom in on early-modern Jain views regarding rituals at death and particularly Jainism’s opposition to the Hindu śrāddha ritual. This ritual at the conclusion of the funerary rites involves the offering of gifts and food to the ancestors and priests so that it may benefit the deceased onto his next life as well as the donor. The paper will analyse a specific short story that criticizes śrāddha from the Dharmaparīkṣā by the Digambara Jain Manohardās, which is a vernacularisation of the 10th c. Dharmaparīkṣā by Amitagati. This story is interesting for how it embeds its critique into an episode of a merchant’s life as well as an origination story about a goose and a crow that is not found elsewhere. Through its different layers of story, the text presents the multiple values attached to a critique on śrāddha. In order to evaluate Manohardās’ depiction of the Hindu ritual, this paper will also engage with other discussions of śrāddha including Somasena’s contemporary Sanskrit Traivarṇikācāra (Dundas 2011) and Somadeva’s late-medieval Yaśastilaka. The paper will suggest that an early-modern narrative argumentation against the ancestral ritual as that by Manohardās is not just a continuation of a time-honoured topic, but instead a reframed engagement with the multireligious past as well as the early-modern lay-focused present.

Manpreet Kaur, Columbia University

Farid Parcī by Anantadas

In this paper, I will discuss the newly discovered hagiography of Baba Farid, a Chishti Sufi from the 12th century CE, attributed to the author Anantadas. While this relatively recent finding (the manuscripts are now housed at Rajasthan Shodha Sansthan, Jodhpur) expands Anantadas’s oeuvre, it also hones his hagiographical focus to the specific regional network of sants in the western region of the Indian subcontinent. Baba Farid, hitherto genealogically linked to Chishti Sufis in the malfuzat literature or associated with Punjabi literary and devotional traditions, is connected here to vernacular Rajasthani sants. Moreover, the manuscript in which this parcī has been found also includes life-narratives of Rajasthani female saints such as Karmā Bāī, Karmātī Bāī, Kistūrī Bāī, Phūlī Bāī, etc (though by a different hagiographer). So, on the one hand, this phenomenon of accretion and expansion of the parcī corpus of Anantadas appears similar to the way Kabir, Nanak, or Mirabai’s corpora grew over time in the written archive of Bhakti. On the other hand, this new corpus points to a fleshing out of the local bhakta and santa network connecting places such as Bikaner, Khandela, and Shekhawati through this hagiographical corpus.

David N. Lorenzen, El Colegio de MexicoKabir and Islam

Kabir and Islam

This paper will argue that the historical connection of Kabir with Islam was likely stronger than scholars usually admit and that his dominant position, however inconsistent, was to advocate an independent religious identity that was neither Hindu nor Muslim. In the older collections of his songs and verses, Kabir does favor Hindu names for God, most often the name Ram, but he also uses Muslim names. He frequently employs Yoga terminology, but his views about Yoga are quite ambiguous. He directs his worship to a nirguni God, one without form and, in most passages, without an active persona. Recent Kabir Panthi intellectuals usually connect this nirguni God with the Advaita Vedanta concept of Brahman, but this identification is not wholly convincing. Beyond the fact of Kabir’s worship of a single God without form, it is difficult to identify the probable influence of Islamic ideas on Kabir. Nonetheless, we do know that he was raised in a Muslim family, that he once had Muslim followers, that he had contacts with some Muslim Sufis (most notably Sheikh Taqi), and that he was evidently influenced by the Ismaili version of the set of ten avatars (although Kabir rejects the identification of these avatars with God).

Anne Murphy, University of British Columbia

Assessing Gurmukhi cultural production in the late early modern period: the case of the Vicārmālā in the field of “Greater Avaita”

The field of Vedanta was particularly productive across communities in the early modern period – as Christopher Minkowski notes, “a lot was written about non-dualism, often at great length and sometimes with great intellectual and polemical force.”[i] This led, in part, to the compilation of catalogs and surveys that explored the variety of Advaitan positions in a synthesizing mode, “towards the generalization of regional arguments and arrangements in religious matters.”[ii] Minkowski notes that in the earl modern period, Advaitan activities were concentrated in the South, largely in association with the Sṛṅgerī and Kāñcīpuram maṭhas (monasteries), which developed with the support of the Vijayanagara state.[iii] Later Benares evolved as a major centre, one that provided for the learning and rise of Niścaldās (ca. 1791-1863), whose vernacular Ocean of Inquiry (Vicāra Sāgara)contributed to a “Greater Advaita Vedanta” that Michael Allen has described, which incorporated vernacular works, non-philosophical works, and works that integrated with diverse traditions such as bhakti, Sikhism, and yoga.[iv] This was a part of the proliferation of Advaita thought across languages and scripts in north India, and its influence in Gurmukhi domains has been considerable, if underexamined; Jvala Singh’s forthcoming work on the Suraj Prakash, by Santokh Singh, will be instructive in this regard. The Nirmala and Udasi intellectual communities in Punjab and beyond, for instance, were strongly influenced by Advaita thought. We can perhaps put in this category of “Greater Advaita” the Vichārmālā attributed to Anantadas, which was translated by Lala Sriram and published from Calcutta in 1886; it is unclear if this work was authored by the well-known Anantadas who was author of the Kabir and other parachais in the first half of the 17th century.[v] This text is extant in the Wellcome Collection in the UK, and numerous copies—a total of seventeen—also are present in the Bhasha Vibhag Collection; two by an Anantapuri are available on the Punjab Digital Library website.[vi] It was clearly a well-known text in its time in Punjab, and was also well attested in print in the colonial period, as is visible in the British Library collection of printed books in Gurmukhi. This paper will explore this text in preliminary terms, to account for its content within a broader understanding of “Greater Advaita,” and the breadth of its appearance in Gurmukhi manuscripts and printed editions.

[i] Christopher Minkowski “Advaita Vedānta in early modern history,” South Asian History and Culture 2, 2 (2011): 205-231, see pg. 205.

[ii] Minkowski “Advaita Vedānta” 212, 222 for quote.

[iii] Minkowski, “Advaita Vedānta,” 218-9.

[iv] Michael S. Allen “Greater Advaita Vedānta: The Case of Niścaldās,” International Journal of Hindu Studies 21 (2017): 275-297; see pg. 291. See the emerging work of Jvala Singh (University of British Columbia) on Advaita Vedanta in Sikh contexts.

[v] Lorenzen Kabir Legends 10.

[vi] See translation and discussion available at: https://sikhnationalarchives.com/book/the-vichar-mala/; translation also available at: http://www.panjabdigilib.org/webuser/searches/displayPageContent.jsp?ID=11718&page=1&CategoryID=1&Searched=W3GX 3 manuscript versions are on the Punjabi Digital Library. One has different authorship: http://www.panjabdigilib.org/webuser/searches/displayPage.jsp?ID=1&page=1&CategoryID=3&Searched=. The others by Anantha Puri: http://www.panjabdigilib.org/webuser/searches/displayPage.jsp?ID=1233&page=1&CategoryID=3&Searched= and http://www.panjabdigilib.org/webuser/searches/displayPage.jsp?ID=1567&page=1&CategoryID=3&Searched=.

Christine Marrewa-Karwoski, Columbia University and Murad Mumtaz, Williams College

Sensing the Sacred: Ascetic and Visual Vocabularies in Early Modern Rajasthan

Wellcome Library’s Hindi MS 371, the earliest known illustrated codex of Nath, Siddha, and Sant teachings, has proved to be a puzzle for scholars. Originally mistakenly labeled and sold to the library as an “Ancient Buddhist Priests Ms. Book,” it is, in reality, a 1715 CE composite manuscript. In addition to including Sant and Siddha homiletics and poetry, it is also a visual and literary expression of yogic asceticism and spiritual engagement between religious communities. Of particular relevance are two illustrated texts illustrating ongoing dialogues with Indo-Muslim audiences. Said to be transcribed by a Gujar Gaur Brahman in the Dadupanthi monastic center of Narayana, the majority of what is extant of this pothī is dedicated to yogis and siddhas associated with the Nath community. In fact, of the thirty-one paintings in this manuscript an astounding twenty-three are images of Nath yogis. To complicate an easy reading of the manuscript, there are also images of Muslim saints, that are occasionally even supported by Persian labels.

This paper aims to contextualize the literature and the artworks contained in the manuscript. By presenting and analyzing them together, this interdisciplinary research identifies the various influences embodied in the text, and conjectures how and for whom this manuscript was constructed. The mixed linguistic registers used in the pothī, along with the unconventional orthography and one sided illustrated folios suggests that this manuscript was originally employed to narrate the teachings and stories of a variety of saints and yogis to not only the owner of the manuscript but to different publics. A close visual analysis helps identify the stylistic choices made by the artists. In particular, the paper examines how scribes and artists working on the manuscript adapted a shared North Indian visual and ascetic vocabulary and translated it into a local Rajasthani idiom.

Murad Khan Mumtaz, Williams College

Dastan-i Kabir: The Enduring Legacy of Kabir in 18th– and 19th-Century Muslim South Asia

Kabir has been valorized in South Asian popular culture through the medium of devotional poetry sung across the Subcontinent in the form of ghazals, bhajans, and qawwalis. He was also a beloved devotional figure of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Muslim nobility, and is an important representative of Bhakti expression. Kabir himself resisted being categorized as either “Muslim” or “Hindu,” yet both groups continue to revere him in popular culture to this day.

Using an interdisciplinary approach, my paper presents and discusses material that sheds new light on the reception of Kabir in Muslim South Asia. Building on my recent research on 16th– and 17th-century sources, in this presentation I highlight 18th– and 19th-century visual and textual evidence. In particular, I introduce a manuscript I came across recently in the Punjab University Library, Lahore. The hitherto unknown text is a Persian hagiography of Kabir written in the form of a “dastan” or legend. In order to contextualize the text, labelled Dastan-i Kabir in the Library catalogue, I compare it with some important North Indian paintings depicting Kabir, made for Muslim elites at around the same time. How does the image of Kabir change with the linguistic shift from Hindi to Persian? Does the text rely on Indic terminology when narrating Kabir’s spirituality, or does the unknown author use Sufi terminology shared within the larger Persian cosmopolis? Are there any overlaps between the visual and textual representations of Kabir, or are these two completely different spheres of patronage and reception? These are some of the questions that have motivated my research. In short, by examining key literary and visual primary sources I discuss how one of the most important medieval poets of South Asia was positioned and re-imagined within the framework of Indo-Islamic devotional culture in the 18th– and 19th-centuries.

Hiroko Nagasaki, Osaka University

Another Sūrdās

Sūrdās is a legendary blind poet of Krishna devotion, an Aṣṭachāp (eight seals) of the Vallabha Sampradāy. His anthology Sūrsāgar is one of the most important works of early Hindi devotional literature. Even though it has not drawn much attention, some hagiographies tell that in the same Braj region and in the same period as this famous poet, there was another Brajbhasha poet named Sūrdās. It is common that there are bhakti poets of the same name. Apparently, there was confusion from olden times, for the poetry of the lesser-known Sūrdās is incorporated into the Sūrsāgar, as Ramchandra Shukla already pointed out in his book Hindi Sahitya ka Itihas. Our question is who this other Sūrdās was. In Nābhādās’s Bhaktmāl, there are two chappayas (six-line poem) about a poet named Sūrdās: chappaya 73 has been interpreted as a reference to the blind poet Sūrdās, in which there is not much information about him other than his poetic skill, and chappaya 126 refers to the poet’s devotion to Madanmohan. While Priyādās, the first commentator on Nābhādās’s Bhaktmāl, did not comment on chappaya 73, he described in the commentary on chappaya 126 that Sūrdās Madanmohan was an amīn (inspector) of Sandila. According to Nābhādās, Sūrdās Madanmohan composed the pada in which he described himself as a guardian of the sants’ foot (shoes) and explained how he came to Vrindavan to devote himself to Mahāprabhu. My paper will portray the two figures called Sūrdās based on the different hagiographical sources, i.e., the Chaurāsī Vaiṣṇavana kī Vārtā of the Vallabha sect, and the Bhaktmāl by Nābhādās and its commentary. Finally, I will try to elucidate the characteristics of the alleged works of Sūrdās Madanmohan edited by Prabhudayāl Mīital.

Luther Obrock, The University of Toronto

Stories About Buildings and Things: Material Culture and Sanskrit Poetry in 15th Century Kashmir

In the latter half of the fifteenth century, the reign of Sultan Zayn al-‘Ābidīn (r. 1420-1470) of Kashmir was memorialized in two Sanskrit works, the Rājataraṅgiṇī of Jonarāja and the Jainataraṅgiṇī of Śrīvara. Far from simple Sanskrit royal praise poems, these texts engaged with new political, social, and material forms through often audacious literary experimentation. While these histories document and comment upon the changing religious and cultural landscape in Sultanate Kashmir, they also present specific arguments for ideal sultanate kingship and societal structures. Writing under the Shāh Mīrī Sultan Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, Jonarāja and Śrīvara creatively and carefully positioned their writings within the history of elite Sanskrit (particularly Kashmiri Sanskrit) literature while speaking directly to contemporary events and concerns of an increasingly Islamic and Persianate kingdom.

To bring their views on Sultanate Kashmir into sharper relief, this talk will present close readings of Jonarāja and Śrīvara’s Sanskrit poetry in relation to new material realities and architectural forms under the Sultans. In their attention to built spaces and material circulation, these authors allowed history to enter into their texts and to engage with the everyday politics of Sultanate Kashmir. This talk will place Jonarāja and Śrīvara’s Sanskrit accounts in conversation with a range of sources from Sultanate Kashmir, including Persian texts, built spaces, material culture, and epigraphy. A sensitively contextualized reading of Jonarāja and Śrīvara’s histories offers insight both into the complex processes underlying elite representation in Sultanate Kashmir as well as into the ways in which the expressive power of Sanskrit was harnessed, expanded, and challenged after the stabilization of Islamic dynasties in South Asia. Sanskrit in Sultanate Kashmir thus provides a vantage for understanding the possibilities of intercultural exchange and representation in Early Modern South Asia.

Kiyokazu Okita, Sophia University

Rādhā’s Moral Discourse: Contextualizing the Extramarital Relationship in Baḍu Caṇḍīdās’ Śrīkṛṣṇakīrtan

“O Baḍāyi! Kṛṣṇa wants to embrace me. If he touches me, I shall give up my life […] Prohibit Kṛṣṇa! Make him give up his hope to be my husband (Dān-khaṇḍ 4)” says Rādhā to her elderly caretaker in Caṇḍīdās’ Śrīkṛṣṇakīrtan. Together with Vidyāpati and Jayadeva, Caṇḍīdās was one of the favorite poets of Caitanya, the charismatic inaugurator of Bengali Vaiṣṇavism (De 1961: 112). Current scholarship agrees that the text was written in the latter half of the fourteenth century (d’Hubert 2018). As the earliest surviving Vaiṣṇava text written in Bengali (Klaiman 1984: 11), Caṇḍīdās’ work occupies a significant place in the development of early modern Vaiṣṇavism in Bengal and beyond (Kitada and Tamot 2013). Perhaps a typical image of Rādhā familiar to us today is that of the ideal devotee who is passionately dedicated to the mischevious cowherd (Coleman 2018; Wulff 1996). Surprisingly, however, Caṇḍīdās’ Rādhā harshly rejects Kṛṣṇa again and again, clearly expressing her annoyance, upset, and even sense of disgust towards him. Trying to dissuade him Rādhā refers to her marital status and points out her family relation with him. In the narrative, Kṛṣṇa is Rādhā’s nephew since Rādhā is married to a cowherd by name of Āihan, who is the brother of Kṛṣṇa’s mother Yaśodā. It is this kinship between Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa as well as the extramarital nature of their relationship that makes Kṛṣṇa’s sexually charged approach socially transgressive. By examining Rādhā’s statements and her interaciton with other protegonists this presentation attempts to clarify the boundry of social acceptability in Caṇḍīdās’ work. By so doing, I hope to situate the so-called “vulgarity” of the Śrīkṛṣṇakīrtan (Knutson 2019) in a larger discussion on the extra-marital relationsihp (parkīyā-vāda) in Kṛṣṇa devotionalism that became controvertial in the early modern period (Okita 2018, 2020, 2021).

Rosina Pastore, Université de Lausanne

“For the benefit of people”: Bhuvadev Dube’s (19th c.) Hindi translation of Brajvāsīdās’s Brajbhāṣā Prabodhacandrodaya Nāṭaka (1760)

The late 19th century saw a proliferation of translations of earlier literature into Hindi, Urdu, and Persian, published – among others – by the notable Lucknow publisher, Naval Kishor Press. At the time, intellectuals like Bhartendu Harishcandra (1850–1885), preoccupied with building a canon for Hindi literature, called for a return to Sanskrit literary models adapted to “modern needs” (Dalmia 2015). However, my paper sheds light on how the nearest literary reference for the translators could well be bhāṣā texts. In particular, I examine the Prabodhacandrodaya drama translated by Bhuvadev Dube and published in 1895 by the Lucknow house. Bhuvadev Dube did not translate from the Sanskrit Prabodhacandrodaya, composed by Kṛṣṇamiśra in the 11th c., but rather from Brajvāsīdās’s Prabodhacandrodaya Nāṭaka, written in 1760 in Brajbhāṣā and published by Naval Kishor in 1875. I will show this by focusing on the preface to the translation and on the process and strategies of translations adopted by Dube, showing his experimentations with language. Besides this, I analysed the content in order to show what a chiefly philosophical and religious drama like the Prabodhacandrodaya could become in a period of transition and negotiation of languages and identities.

Heidi Pauwels, University of Washington

Recovering the Voice of “India’s Mona Lisa”

“India’s Mona Lisa” refers to one of the portrayals of the goddess Rādhā from the elegant Kishangarh school of Rajput Painting, as well as to the purported model for that “portrait.” A court performer in the Rajasthani principality of Kishangarh in the eighteenth century, she was known by her nickname of Banī-ṭhanī, or “Miss Made-up.” Hers is the fascinating story of a young slave girl, trained in music for Kishangarh’s queen’s entertainment, who ended up a favorite concubine (pāsbān) of the queen’s stepson, the crown-prince Sāvant Singh (1699–1764). He was the patron who commissioned the most famous Kishangarhi paintings to illustrate his own Classical Hindi devotional poetry, which he signed as Nāgarīdās. It has been surmised that this portrait too was based on one of his poems, where he ascribed the looks of his concubine to Rādhā. This paper reports on the process of recovering the concubine’s own voice, as she wrote under the penname of Rasikbihārī. I am doing so on the basis of newly discovered manuscript materials. The goal is to go beyond the pretty images to allow her to take her place in the history of Classical Hindi literature as an author in her own right.

Rabi Prakash

‘Political’ Hagiography in Vernacular: History and Ideology in Early Modern Brajbhasha Carit Kāvya

Hagiography constitutes an important literary genre in early modern India. However, for our modern historical sensibilities, hagiography as an intellectual artefact of pre-modern times, remains the anti-thesis of historiography and not a subspecies of it. While early Hindi hagiographies of Bhakti sants have been examined for what they ideologically represent (Hawley 2000, Burchett 2009), the hagiographies of regional Hindu kings of Mughal India are rarely read for what they historically meant and represented. Almost every important regional political ruler commissioned a hagiography of his own at his court. This paper examines the motive and context of the production of these texts. To distinguish from sant hagiographies and to note their distinct historical and political objectives, these texts are termed as ‘political hagiography’ here.

In the Mughal imperial structure, native Hindu rulers did not only enjoy the right to high official positions in the mansabdari system, but they were also entitled to secure watan jagir in lieu of their allegiance to the Empire. The award of watan jagir, exclusively available to native Hindu rulers, amounted to the recognition of their territory as ‘patrimonial lands’. Akbar’s policy of awarding watan jagirs rested primarily on the condition that a regional ruler’s family had ruled over the lands for generations, and their quintessential credentials of being ‘kshatriyas’. Such a policy leads to political interests in creating royal genealogies and claiming credentials of being a kshatriya, which manifested intensively in the literary and intellectual culture at the regional courts.

The paper argues that the composition of political hagiographies emerged not only as an important tool for appropriating kshatriya status and reconstructing royal genealogies to bolster one’s kshatriya status claim, but also more fundamentally they served as authoritative texts for the quest of legitimate political power over a given territory (bhumiyāvaṭ) among the political entrepreneurs of 17th and 18th century.

Ravi Prakash, Independent Scholar

Housing the Rajput: Innovation in the Baramasa of Keshavdas

Keshavdas, the court poet of the Bundelas, included a baramasa in his riti-granth, Kavipriya. But he inverted the temporal structure associated with the genre of baramasa – the heroine enjoys the company of the hero with the possibility of viraha looming in the future. Scholars have understood this change as a case of adaptation of the model of sad-ritu-varnan. Arguing against such a stance, in this paper, I propose that Keshavdas’s innovation is rooted in his attempt of writing an alankara-shastra modeled on Dandin’s Kavyadarsha. In presenting his baramasa as an example of Aakshepa alankara, Keshavdas makes two simultaneous moves which mirror each other. In the world of his poem, the wandering nomad is housed as a courtly Rajput; while the baramasa (a genre rooted in nomadic life) is housed in a riti-granth (a genre rooted in courtly life). I further speculate that his innovation might be resonant with the change in the status of his patrons (the Bundelas) from a mobile war-band to courtly Rajputs. I look into the historical poems written by Keshavdas as well as existing scholarship on Rajput architecture and paintings to substantiate on my speculative argument. Ultimately, drawing upon Molly Aitken’s framework of the ‘intelligence of tradition’, I put forth an understanding of Keshavdas which is centered on his creative agency and doesn’t restrain him in the binds of derivative conventionalism.

Maria Puri, Independent Scholar and Translator

Cūkā gauṇu miṭiā ãdhiāru, guri dikhlāiā mukti duāru…: Mystical ascent through divine word in Guru Arjan’s hymn in Rag Parbhati

The proposed paper is a part of a larger study of editorial frames at work in the Rag Parbhati section of the Guru Granth Sahib. While my earlier analysis (Puri, forthcoming) focused on the five hymns of Kabir (GGS: 1349-1350) — and their consummate arrangement and dialogic character — current presentation looks at Guru Arjan’s hymns, with special reference to the hymn which directly precedes those of Kabir and from which the line quoted in the title is taken. As Guru Arjan is credited with producing an authoritative text of the Adi Granth (1604), it might be instructive to see how his own hymns frame and explicate themes set out in earlier compositions found in the same section, which besides hymns of the gurus, contains also hymns of three bhagats. Keeping in mind the very closely knit arrangement of Kabir’s hymns in Rag Parbhati, of which the middle three are attested to in other Kabirian collections (Callewaert 2000), I try to explore if similar phenomena might be at work in the whole Parbhati section, and, by implication, other sections of the GGS. This might provide novel information on the inner workings of editorial strategies aimed at aligning clusters holding the compositions of the preceding gurus with the carefully tailored selections of the compositions by the bhagats, all the while using one’s own (Arjan’s) hymns as a kind of ‘connective tissue’. Even as a working hypothesis, the study might help to work out a provisional template used for the placement of hymns or their clusters within the larger scriptural entity informed by the highly specific theological worldview of the Gurus.

Callewaert, Winand M., Swapna Sharma and Dieter Taillieu, 2000, The Millenium Kabīr Vānī, New Delhi: Manohar, 2000.

Puri, Maria, (forthcoming), “Avali Alāha nūru ūpāiā: Kabīr Bāṇī in the Early Modern Devotional Practices of the Sikhs.”

Puri, Maria, (forthcoming), “Sunn sandhiā terī dev devākar adhapati ādi samāī…: Vocalizing the Ineffable in the Guru Granth Sahib.”

Mahipal Singh Rathore, Jai Narain Vyas University

Junjhar Worship and early Hindi Literature

This paper engages with the idea of “Junjhar,” warrior and deification and the trope related with phenomena as it appears in early modern Hindi and Rajasthani literature. In the early Indian history we come across valiant warriors who fought for a noble cause and whose memory continued to live in literature and folklore. The paper explores how such courageous and valorous warrior called ‘Junjhar’ are worshipped at two places. One where their head was cut off and the other where the torso fell on the ground. These warriors became folk-deity and worshipped differently than the Mythological (Puranik) god and goddess. The study shall also examine how jujhars finds mention in host of historical narrative, annals, anecdotes, khyatas, folk songs, and many celebrated classics. For example Saint Kabir in his “Suratan ke Aang” and Malik Muhammad Jayasi in his “Padmavat have used the trope. the paper consequently delves deep into early Hindi and Rajasthani literature to purport the significance, and position of ‘Jhunjhar’

Akshara Ravishankar, The University of Chicago

Tell me that Tale: Form, Genre and Scholasticism in Two Early Hindi Bhagavad Gītās

In this paper, I examine two early Hindi versions of the Bhagavad Gītā dated to the 16th and 18th centuries respectively. The Bhagavad Gītā has a long tradition of being approached as a scholastic text in Sanskrit, beginning with the first extant commentary on the work by Śaṅkara in the 8th century CE. In the early modern period in North India, we see the emergence of vernacular versions of the Bhagavad Gītā, bearing complex relationships with both the source text and with Sanskrit scholastic traditions. This paper will analyze sections from two texts in particular: one by an author named Theghnāth rendering the Bhagavad Gītā in the Gwalior court in the 16th century, and another by an author named Ānandrām, who produced a widely circulated translation of Śrīdhara Svāmin’s commentary on the Bhagavad Gītā. While Theghnāth describes his Gītā as a kathā, poised to provide guidance for a prince, Ānandrām’s text frames itself as a commentary, even as it renders a prior scholastic work.

Focusing on questions of genre that arise in these two instances of early modern vernacular Gītā production, I examine the protocols vernacular authors used to transmit the Bhagavad Gītā to their newer audiences during this time. I argue that the ways in which these vernacular texts framed their source text(s) and ultimately engaged with their different audiences, making choices in what to include and omit, thus re-framing the Gītā itself, produced new levels of meaning in the process of translation. I conclude by asking how these emerging protocols of commentary and translation in early Hindi, drawing from Sanskrit commentarial traditions, impacted and mediated the Bhagavad Gītā’s canonical status, occupying space as both a scholastic and a popular text.

Swapna Sharma, Yale University

Vallabharasik: A creative Bhakt

Vallbharasik was a great saint- poet who was extremely infatuated by Radha and Krishna’s love. He was a worshiper of Nikunj- Bihari young couple yet he was so deeply immersed in their love mentally unable to cross the threshold of Nikunj, the space of Divine play. Although he was born and brought up in a well-established and respected Chaitanyaite lineage of Gadadhar Bhatt (1515-16-10) of Vrindavan, yet he was beyond the sectarian boundaries.

In this paper, some aspects of Vallabharasik’s legendary life and unique personality will be shared. Particularly, I would like to explore his wonderful and versatile poetry. He has composed verses on various topics- Dussehra, Diwali, Holi, Rakhi, Jhoolan, Sanjhi, Chandan yatra, Rath Yatra, Varsha and so on. No matter how versatile the content is, it is completely drenched in

love of Radha Krishna, always busy enjoying Yugal Mahal Ras that everything is created within the limits of Nikunj. He himself announced, ” Ham jugal mahal raslinda, kunj Alinda ulaghi na jaanen”.

His famous two long poems are- ‘Suratollaas’ and ‘Barah baat Athaarah Painde’. Suratollaas is a fine example where Radha and Krishna’s euphoric gaiety, their pure love has been expressed with great subtlety, depth and intensity and “Barah baat Athaarah Painde” expresses the climax of love. This poetic composition describes in various ways that in the city of love rules are just opposite from this world. The love expression through eyes makes this piece of poetry so unique. Vallabharasik has used various different meters to compose his love poetry but he is particularly known for using Manjh.

Akansha Singh, Ashoka University

Afghans and the Politics of Alliances in Early-Modern South Asia, c. 1585-1612

In early modern South Asia, the Afghans shared a fraught relationship with the Mughal Empire. Several Afghan groups resisted Mughal authority, while some also allied with the empire. In this context, this paper will investigate the utility of the concept of fitna in helping us make sense of this complex history. It focuses on the actions of the Afghans in relation with Mughal wars directed against them between 1585, which marked the Mughal annexation of Kabul and the beginning of Akbar’s campaigns against the Afghans of Afghanistan, and 1612—when Khwaja Usman, an important Afghan zamindar was defeated by Mughal forces in Sylhat in eastern Bengal.

In this paper I also intend to ask whether the Afghans, in the late-sixteenth and early- eighteenth centuries, behaved as one community, who stuck together as a community, or operated as more splintered sub-groups.

The paper will be based on two literary texts: Abul Fazl’s Akbar-nāma which is a detailed biographical account of the reign of Mughal emperor Akbar. The second is Mirza Nathan’s Bahāristān-i Gh ā’ibī. It is a neglected source on the history of the Mughal campaigns in eastern India during the early-seventeenth century.

The paper will have two sections, focusing respectively on the Afghans in Afghanistan and the Afghans in Bengal. The region of Afghanistan denotes the mountainous region located roughly to the south and east of Hindu Kush and to the north and west of the Indus River. This is the earliest attested homeland of the Afghans. The part of Bengal that I have taken into consideration was known as “Bhati” or East Bengal. This area included the entire delta east of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly River and roughly corresponds with modern Bangladesh.1

1Richard M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 146.

NAGWANT SINGH, University of Delhi

Potentiality of the Rasprabodh: Revealing Interiority and Emotional Community(ies)

This paper will historically analyze the career and background of Sayyid Ghulam Nabi Bilgrami (c. 1699-1750 CE) famously known as ‘Raslin’, who belonged to the Qasbah Bilgram. Raslin was associated with the court of Abul Mansur Mirza Muhammad Muqim Ali Khan (c. 1708 –1754 CE), better known as Nawab Safdar Jang. In this paper, an attempt has been made to understand the role of Qasbah Bilgram which played a seminal role as connective tissue for the bhakha literary network of early modern North India. It will convincingly establish that the engagement with Raslin’s oeuvre is like open sesame; would be a worthy enterprise as far as the operational aspects of bhakha literature are concerned. Raslin has been credited with the texts namely Angdarpan (Mirror of the body, 1737), Rasprabodh (Understanding of sentiments, 1742), and Mutafarriq Kabitt or Phutkal (Miscellaneous poetries). Rasprabodh is the main focus of this paper, it has 1154 dohas (poetic meter). In this poetic manual, there are some of the well-known sub-genres such as Nayak-nayika bhed, Barahmasa, Sad-ritu varnana, etc. In that context, it will explore the very causality behind the processes that were responsible for the production and circulation of bhakha texts. As far as the genre is concerned, Raslin says he is writing a Rasgranth and named it Rasprabodh. This source deals with the emotional contents; the paper will try to unravel the mechanisms that were responsible for the making of emotional knowledge and its social settings. In that respect, careful textual analysis helps to make sense about the interiority of the text that further leads us to its contextualization i.e., the relationship between language, text, and literary space. In a nutshell, it will convincingly try to establish that canonical understanding of the early modern bhakha literary culture leads us somehow into the state of cultural amnesia and also try to understand the aspects of literary activities of early modern North India that are nuanced, layered, and complex.

Raman Sinha, Jawaharlal Nehru University

Songs & Dance: The songs of Bindadin Maharaj and the evolution of Kathak in 19th century

Pundit Bindadin Maharaj (1830-1918) is widely credited as the pioneer in establishing Lucknow gharana of Kathak dance in 19th century Awadh. He was not only a great practicing dancer but also a great song composer and when he realized that under the pretext of technical sophistication, rasa or bhava aspect of the dance is being neglected, he himself wrote so many songs and composed it with subtle fineness that later became hallmark of the Lucknow gharana.it is said that he composed almost five thousand songs (bandishes) on different musical styles such as Thumri, Bhajan, Dadra, Sadra, Holi, Tarana, kheyal, Tappa, Pada, Jhoola etc., but unfortunately very few songs have survived. These songs were later collected and published by Birju Maharaj in a book called Ras Gunjan. This book contains thirty songs primarily based on early-modern Braj themes of Hindi literature, i.e. Krishna-leela, Nayikabhed, Ashtayam etc. The questions of my enquiry would be whether these compositions are merely dance-syllables for a performance or it has some literary quality with some poetic merit of its own? Another supplementary set of queries that this study will try to address is whether the theme and tenor of these songs presupposes material or spiritual nuances of the performance or not, as it is generally believed that the Jaipur gharana of Kathak is religious or spiritual whereas Lucknow gharana is erotic or material.

Jaroslav Strnad

Reflections of Kabīr in the early Dādūpanthī and Sikh spiritual paths

The paper has chosen as its point of departure the oldest extant textual corpus produced by adherents of one newly emerging religious community, the Dādūpanth, in early 17th century Rājasthān. Dādūpanthīs interacted with a number of other groups and communities whose area of activity was either partly coextensive with theirs (Nāthyogīs, Vaiṣṇavas), or closely adjacent – the Sikhs. One of the important issues both Dādūpanthīs and Sikhs had to deal with was yoga and related individual paths to the highest spiritual goals. Both had to formulate their own position toward its most prominent representatives, the Nāthyogīs. Apart from a great deal of common ground, both differed from the Nāths in important points including the role of individual effort versus divine grace in reaching the ultimate stage of the spiritual journey, and also the question of the very nature of the ultimate experience. How did these two panths shaped their attitudes to these questions during the formative stage of their development? Both were from the very beginning open to all members of society, irrespective of their previous or current religious affiliation, caste and social standing. As a degree of controlled internal consistency was the necessary basis for development of common identity, answers had to be specific and as far as possible internally consistent. At the same time, toleration of a degree of internal difference might generate a more universal appeal, perhaps at the expense of internal cohesion and consistency. Different approaches to this problem seen in the Gurū Granth on the one hand and the early Dādūpanth on the other are reflected ia. in the way the name of Kabīr was invoked as an authority in support of particular positions taken by different participants in the debate.

Radosław Tekiela, University of Warsaw

Wandering in the Indian romances

Wandering has been long held as one of the defining characteristics of “romance” (as defined by Parker 1979, Fuchs 2004). It has been proved that wandering – whether of characters or the narrative – often has the decisive consequences for the reading of the romances. While this view has been recognized by the scholars working on individual Indian romances (e.g. de Bruin on 2012 or Behl on 2012), as of now there is no comprehensive work on the subject has emerged to date.

This paper will be concerned with the significance of the wandering in the Indian romances. There are episodes of when the hero loses his way, of “metaphorical wandering” such as whenever the hero strays under the impression of a statue of the heroine, and of the “structural” wandering embedded in their episodic structure of the work. The paper uses material from Jan’s various lesser-known sources – e.g., including shorter romances of Jān (fl. 1614-64), such as Tamīm Ansārī, Rūpmañjarī and Nūr Muhammad’s Anurāg Bā̃surī (1764) – in an attempt to find the preliminary answer to the question of whether the structural elements of romance play a role in the ideological message of the poems, or rather whether they are more represent an effort to add tension to the romance, and keep the audience engaged.

Aleksandra Turek, University of Warsaw

Individuality against Collectivity: Pragmatic Goals of Ḍiṅgaḷ gīt Literary Compositions

In my paper I aim to ponder on the genre of Ḍiṅgaḷ gīt – commemorative poems, which form the bulk of Rajasthani literature in old Marwari (16th-19th centuries) – and to show the poems as works composed to immortalise certain individuals, ordinary beings first of all (Rajput warriors, petty lords, landowners) and their acts, deeds, or achievements. The existence of a large number of the Ḍiṅgaḷ gīt stands in contrast to a generalized opinion that the notion of collectivity encompasses almost all aspects of life in India. Such an approach in Indian society through caste, class, community, and religious categories results in not bringing individuals to the forefront. I argue that the Ḍiṅgaḷ gīt, together with Rajput chronicles (khyāt) and genealogies (vaṁśavalī), served locally oriented Rajput politics as another way and attempts to confirm someone’s individual rights to rulership in the jagirdari and zamindari systems of land distribution. However, being a highly sophisticated poetry, aesthetics was not the ultimate purpose of the Ḍiṅgaḷ gīt,but only the way to obtain very pragmatic goals, namely enhancing reputation and due to this legitimizing power.

Julie Vig, York University

Mapping a Sikh Landscape beyond Punjab: Literary Geographies and Community Formation in Gurbilās Literature

Gurbilās literature—which means “the play or pastimes of the Guru”—refers to a collection of historical poems written in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Brajbhasha about the lives of the Sikh Gurus. In this paper, I examine how landscapes and literary geographies are imagined in gurbilās literature in relation to the Sikh Gurus and to the communities that formed around the Gurus. I also interrogate how the travels of the Sikh Gurus, especially those of Guru Gobind Singh, and the emotional responses from communities wishing to connect with their Guru passing through or staying in their city, shape the notion of sacred space (tīrtha), and sketch by extension a sacred geography. To do so, I will look at three case studies or vignettes in Kuir Singh’s Gurbilās Pātshāhī Das which describe a Sikh landscape that included territories that are today not perceived as part of the Punjab-centered Sikh world: Bihar (Patna), Rajasthan (Jaipur), and Uttar Pradesh (Ayodhya). While it is not the goal of this paper to look closely at the specific composition of the social landscape imagined by Kuir Singh and which shaped the Sikh Panth in the late eighteenth century, it does examine how Kuir Singh’s mapping of the Tenth Guru’s travels allows us to discuss the relationship between place and community. Guru Gobind Singh’s travels and encounters also exemplify the complex roles he played as spiritual leader and political figure and as an embodiment of the policy of mīrī-pīrī(temporal-spiritual) articulated by the sixth Guru, Guru Hargobind. Through a discussion of his travels and encounters with powerful figures, I also wish to further illustrate how Kuir Singh’s gurbilās represents a textual microcosm that reveals the complexity of Guru Gobind Singh’s “court” and how it falls uneasily within the fixed categories of “religious” and “secular”.

WANG Jing, Peking University

Research on the Folk Characteristics of the Sūrasāgara

The Sūrasāgara represents a treasure among Early Modern Indian Bhakti literature. Traditional Indian literature highlights the orthodoxy and classicality of the Sūrasāgara as a ‘literati’ work. However, from the perspective of the text’s content, the Sūrasāgara remains quite different from the Rāmacaritmānas, a work of the same period, in that it is far more reflective of everyday life. Moreover, the Sūrasāgara’s creation is closely related to Indian folklore and showcases more folk characteristics. This study examines and illustrates the folk characteristics of the Sūrasāgara based on the following four aspects: its creator, audience, the text’s portrayal of Kṛṣṇa, and its artistic expression. In doing so, this study argues that the Sūrasāgara represents the product of the Vallabha Sampradāya literary community, which combined the Hindu classic the Śrīmada Bhāgavata with the prominent folk elements of “Sur poetry.” The Sūrasāgara utilizes folk literary forms to express its religious purpose. Members of the Vallabha Sampradāya community and modern Indian scholars organized and repurposed these local popular, oral, scattered, and fragmentary “Sur poetry” and eventually compiled them into the Sūrasāgara to promote their ideas and intentions. The fusion of the religious classic Śrīmada Bhāgavata with the popular folk elements of “Sur poetry” by modern scholars further enhanced the distinctive characteristics found in the Sūrasāgara. The Sūrasāgara not only promotes the cult of Krishna, but it also reflects society’s everyday life and the basic aesthetic emotions of the Indian people. Thus the work offers unique insight concerning the timeless value of Indian folk literature and its aesthetics. Based on our investigation of this classic work, we can better consider the fundamental characteristics of Indian folk culture, the rich lives and emotions of Indian society, and Indian peoples’ thinking concerning the relationship between humans and gods and the religious experience seeking liberation.

Richard David Williams, SOAS University of London and Makoto Kitada, Osaka University

The Queen Regent’s Rose Garden: Patronage and Interregnum in the Gulšan-ě-‘išq (1658)

For five years after the death of her husband, Muḥammad ‘Ādil Šāh (r.1627-56), Khadījah Sulṭānah served as the Queen Regent of Bijapur. Like her father, Muhammad Qulī Quṭb Šāh of Golconda (r.1580-1611), Khadījah Sulṭānah was deeply invested in Dakanīpoetry: in 1647, she had invited court poets to compete with their translations of the Persian Ḵẖāvarān-nāmah, and her marriage brought the poets of Golconda and Bijapur into conversation.

Khadija Sultana features prominently in Nuṣratī’s Gulšan-ě-‘išq, which was presented to the Bijapur court in1658, midway through her regency. She is eulogised as an inspirational patron of the arts, appearing before her stepson, ‘Alī II ‘Ādil Šāh (r.1656-72). Her central role is framed using cosmological metaphors and references to Islamic history, connecting her politics and patronage to cosmic motherhood. Given that the text, and later manuscript illustrations, presented a direct correspondence between the fictional king and prince in the poem and the historical rulers, Muḥammad ‘Ādil Šāh and ‘Alī II ‘Ādil Šāh, in this paper, we ask how the Queen Regent was discussed in this Sufi poem, which also features a queen ruling in her husband’s absence. We consider the strategies Nuṣratī adopted in praising both regent and king, and how far the fantastical story of the Gulšan-ě-‘išq speaks to the political context in which it was written.

Tyler W. Williams, University of Chicago

Prāgadās Dādūpanthī: The Career of a Merchant Monk

Prāgadās (Prayāgadās) Bihāṇī (d. 1631 CE) was a householder monk of the Dādū Panth of Rajasthan; he was also a member of an affluent and dispersed merchant community, the Bihāṇī clan (khāṁp) of the Maheśvarī caste. This paper will investigate the significance of both Prāgadās’s poetic works and his life as monk and merchant. As Monika Horstmann and others have demonstrated, merchant communities played a central role in the development of nirguṇ sant religion by providing patronage to monastic orders. Prāgadās, like his more famous fellow monk Sundaradās (d. 1689), is an interesting and important figure because he inhabited both the mercantile world from which he hailed and the monastic world into which he took initiation. His kinship and business connections within the Bihāṇī community helped the Dādū Panth to grow both its monastic and lay devotee population as well as to secure additional patronage. Prāgadās’s monastic and merchant identity also make him an important link between the Dādū Panth and Nirañjanī Sampradāy, both of which courted merchant support and espoused a particular type of devotion that mixed yogic and Nath practices with Vaishnava bhakti. Investigating the writings and lives of figures like Prāgadās helps us to better understand the particular theological, ideological, and social form that early sant communities took.

Tomoyuki YAMAHATA, Hokkaido University

Poems on Holy Places as the Foundation of Old Gujarati Literature

Old Gujarati Literary works date back to the 12th century. Most of the early Old Gujarati literary works were written by Jains and included various genres. Loosely common to these literary works is the belief in Neminātha, which is based on the Kṛṣṇa faith.

In Jain discourses, there was a strong relationship between Neminātha and Kṛṣṇa from the time of the Jain Āgamas. Also, from the third to the eleventh century, a lot of saintly biographical literature was produced, including biographies of all 63 great men of Jainism. As part of this, the stories of Neminātha and Kṛṣṇa were popular.

However, it was not until the Old Gujarati literature that many works dedicated to Neminātha alone were produced. In this presentation, I cite the development of Holy place literature as one of the primary reasons for the creative activities for Neminātha.

Today, the most representative Jain sacred sites in western North India are Mount Girnār, Mount Śatruñjaya, and Mount Ābū. However, their significant temples are not as old as the stories of Neminātha and Kṛṣṇa and were built after the 11th or 12th century. That was the period when the earliest old Gujarati literature was written. During this period, donations to holy places, the construction of temples, and pilgrimages led to the focus on the region’s language, where the holy places existed. As a result, Old Gujarati poetry on sacred places became popular after the 12th century.

In this presentation, I will compare the descriptions of holy places in the biographical literature of saints (Carita literature) with the literature of holy places in Old Gujarati, such as “Revantagiri rāsu” and “Ābū rāsu,” to argue for the importance of the role played by sacred sites literature in early Old Gujarati literature.

Biljana Zrnic, Charles University, Prague / Jagiellonian University, Krakow

Toward a Critical Edition of Sūrdās’ Section in the Sharma Manuscript

The paper describes the upcoming critical edition of poems with attribution to Sūrdās from a microfilm copy of the ms3190, the so-far unedited early Dādūpanthī manuscript composed between 1614-1621, kept in Sañjaya Śarmā Saṅgrahālaya, in Jaipur. The compilation, used as a base manuscript for this edition, represents the second oldest collection at our disposal on Sūrdās’ poetry. It has not been examined in previous studies on Sūrdās’ tradition. The paper shows the manuscript’s peculiarities, the classification of poems, the encountered difficulties, and the thematic predilection of pads in relation to other collections with Sūrdās’ poems. I will discuss the manuscript families established according to their geographical provenance as presented by Gupta and Bryant and introduce the Dādūpanthī compilations into the stream of transmission. Sūrdās’ section in the Sharma manuscript is observed in relation to several other collections, including six early Dādūpanthī compilations containing Sūrdās’ pads composed between 1620 and 1700 (among others the Sarvāṅgi of Rajjab and the Sarvāṅgi of Gopāldās). Available in digitalized

form, the collections are mostly unedited and unexamined. The paper examines their relation to the Sharma manuscript, the contamination cases among them, and their impact on the previously established interpretations of Sūrdās’ poetry, often viewed as primarily relying on Krishna carita and reflecting the saguṇa stream of bhakti.